‘US gov’t is unable to grasp deep links between culture, revolution in Cuba’

This article by Abel Prieto appeared in the Dec. 4 issue of the Cuban daily Granma, with the headline “Culture and Revolution.” Prieto is director of Casa de las Américas, a renowned Cuban cultural institution. Prieto, an author, was the president of the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba from 1988 to 1997. He served as minister of culture from 1997 to 2012 and from 2016 to 2018. He also served as an adviser to Raúl Castro.

Prieto, born in 1950, is respected by several generations of Cuban artists for his unflinching defense of the Cuban Revolution, for speaking his mind and for promoting the revolution’s cultural policy, which he explains is “open, plural, anti-dogmatic and an enemy of sectarianism.”

On Nov. 26 the Cuban government broke up a small “hunger strike” by the so-called San Isidro Movement, a group backed by Washington that looks for ways to undermine the revolution by claiming to speak for censored artists and musicians. The next day some 200 people, including artists, writers and students who are not part of the group, gathered outside the Ministry of Culture in Havana to express concern over the government’s action and to discuss freedom of expression. Thirty participants were invited into the Ministry of Culture for what became a four-hour discussion.

Prieto’s article answers the false picture painted by Washington claiming that the Cuban government represses artistic liberty and freedom of speech. He also takes up the damaging effect of “social media,” an important question for the working class.

The translation is by the Militant.

BY ABEL PRIETO

Not by chance, Oct. 20 was chosen as the Day of Cuban Culture. I remember how, with so much pride, Armando Hart1 stressed the fact that on that date, when the Hymn of Bayamo [Cuba’s national anthem] was sung for the first time, it served to pay tribute to the men and women who are central figures in the nation’s cultural life.2

It showed, Hart said, that the fundamental identification between creators of art and the patriotic, anti-slavery and anti-colonial ideals of 1868 — later enriched by [José] Martí, [Julio Antonio] Mella, [Antonio] Guiteras, and Fidel3 — had been synthesized in a remarkable way.

The victorious revolution in 1959 won enthusiastic support from the overwhelming majority of Cuban artists and writers. Many, even those living abroad, returned to the island to join in building a new world.

Although the aggressiveness of the U.S. began very early — through pressure and threats, attacks, bombings, financing armed gangs, and a fierce media campaign — the revolutionary government did not neglect to advance Cuban culture. It founded ICAIC [national film institute], Casa de las Américas, the National Printing Institute, and the first school for art instructors, while also carrying out the literacy campaign.

As [Alejo] Carpentier4 said, times of loneliness had ended for the Cuban writer and those of solidarity had begun. That’s because the revolution created a massive and eager public for arts and letters. It also gave space to the most genuine and historically discriminated against expressions of popular traditions and to the most audacious efforts in various artistic genres.

Unable to fathom the deep links between culture and revolution, the Yankees repeatedly tried to organize groups of “dissidents” in intellectual circles. But they failed again and again.

The case of Armando Valladares was an act of desperation. He was exhibited before the world as an invalid, a poet prisoner-of-conscience. They even published a highly publicized book of his poems, dramatically titled From My Wheelchair.

But he was neither a poet nor crippled (he nimbly climbed the airplane steps when he was pardoned). He had a murky past in the Batista tyranny’s police and had been sentenced to prison for terrorist activities.

Today, many years later, they present an alleged “movement” (San Isidro), an alleged “rapper” who was prosecuted for contempt, and an alleged hunger strike conducted by a dozen alleged “young artists.” They were backed by a big campaign in the foreign press, in digital media paid to carry out political subversion, and in social media. They had the immediate support of [Secretary of State Mike] Pompeo, [Sen.] Marco Rubio, [OAS General Secretary Luis] Almagro, and other individuals.

Social networks were used to create a rarefied climate, intensely charged emotionally, to arouse expressions of backing and moral support against a supposed injustice.

As studies by many analysts have shown, using social networks to appeal to the emotions brings people into transitory communities of shared feelings. At the same time, it paralyzes their ability to reason, judge, and verify the boundaries between reality and fiction.

Many (most) of those who gathered Nov. 27 outside the Ministry of Culture were influenced by the atmosphere created on social networks. Few knew what actually happened at San Isidro or who was involved. Perhaps some of them had had one or another bad experience and they felt hurt. I think they honestly wanted to have a dialogue with the institution.

Others (a minority) participated with complete consciousness in an operation against the revolution. They used social networking to amplify what was happening and to spread it in a distorted way. Fake news was broadcast about an imaginary crackdown that included tear gas, pepper spray and alleged traps set for participants. They knew that their lies were helping to justify Trump’s policies against their country. Their only interest in “dialogue” was to turn it into news, into a show, and score it as a victory. Some needed to justify the money they’re paid.

However, it’s necessary to clearly separate the comic-strip actions of the marginal elements of San Isidro from what actually happened at the Ministry of Culture. Among the latter, there were valuable young people who must be listened to.

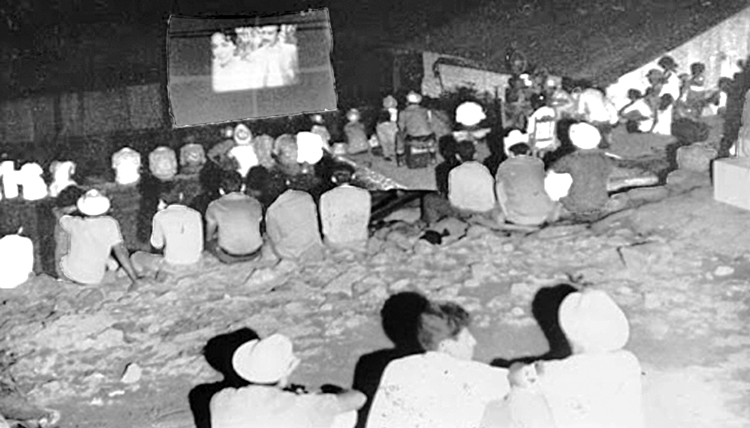

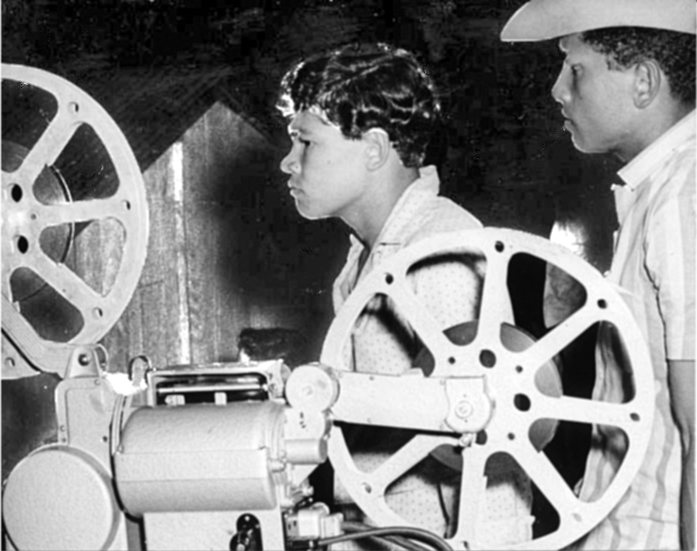

Cuban Revolution fostered widespread interest in “arts and letters” among working people, Abel Prieto says. After the 1959 revolution peasant youth, were trained how to run projectors to show movies, often for the first time, in the countryside, including in the Sierra Maestra.

The cultural policy of the revolution has opened a wide and unprejudiced space for creators to work in total freedom. It’s true that there have been errors, misunderstandings, and blunders, but the revolutionary process itself has set out to rectify them.

These institutions, together with UNEAC [Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba] and the Asociación Hermanos Saíz5 [Saíz Brothers Association], are open to frank discussion with artists and writers. If for some reason this dialogue is interrupted, there are appropriate channels of communication to reopen it.

It’s totally legitimate to discuss how to consolidate the links between artistic creators and institutions. To discuss experimental artistic expressions that haven’t yet been sufficiently understood. To discuss the essential critical function of the artistic creation, the “anything goes” part of the postmodern vision, freedom of expression, and many other topics.

What is not legitimate is disrespect for the law, the attempt to use blackmail against institutions, to disparage the symbols of the nation, to seek notoriety through provocation, to participate in actions paid for by the enemies of the nation, to collaborate with those who work to destroy it, to join the lying anti-Cuban chorus in social networks, and to stir up hatred.

In the midst of the worldwide crisis created by the pandemic and global neoliberalism, Cuba also confronts unprecedented harassment from the U.S. That’s why they’ve chosen this particular moment to finance spectacles that distort the image of our country.

Any artistic creator who approaches Cuban institutions with legitimate objectives will find representatives willing to listen and provide support. With fakes and frauds there is no possible dialogue.

- Armando Hart was one of the historic leaders of the Cuban Revolution. When the revolutionary government established the Ministry of Culture in 1976, he became its minister, serving through 1997. He preceded Prieto as head of the José Martí Cultural Society. Hart died in 2017.

- Cuba’s national anthem was sung for the first time on Oct. 20, 1868. It is also the date when the Cuban independence army freed the eastern city of Bayamo, launching the first war of independence against Spanish colonial rule.

- José Martí — revolutionary, poet, writer and journalist — is Cuba’s national hero. He founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party in 1892. Julio Antonio Mella was founding president of the Federation of University Students and a founding leader of the Communist Party in 1925. Antonio Guiteras was a student leader of the fight against the Gerardo Machado dictatorship in the 1920s and ’30s.

- Alejo Carpentier, a leading Cuban and Latin American writer, is considered one of the best novelists of the 20th century. He returned to Cuba in 1959 and joined the revolution. He served as a Cuban diplomat in Paris until his death in 1980.

- The Asociación Hermanos Saíz is a cultural organization for young people, formed in 1986.